Substance Use Disorder in Primary Care

What is Substance Use Disorder?

Substance Use Disorders (SUDs) are treatable, chronic diseases characterized by intense cravings and compulsion to use despite negative consequences.

This leads to a problematic pattern of use of a substance or substances leading to impairments in health, social function, and control over substance use.

It is a cluster of cognitive, behavioral, and physiological symptoms indicating that the individual continues using the substance despite harmful consequences.3,6 Alcohol Use Disorder is the most common SUD.

SUD is formally diagnosed using the DSM-5 criteria and classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

4 C’s Shortcut

Primary care providers can prescribe evidence-based treatment for SUD. Accurate diagnosis is important because it determines which medications can be prescribed in a primary care setting. Use the 4 C’s Shortcut: Cravings, Compulsion, Use Despite Negative Consequence, and Loss of Control as a shortcut for considering SUD diagnosis.

Why Primary Care?

Given that a significant portion of the population interacts with primary care providers, these settings are crucial for identifying and treating SUD. According to SAMHSA, in 2020, over 41 million Americans had a substance use disorder, yet only 2.7 million received treatment. Primary healthcare settings are well-positioned to support individuals with substance use disorders by providing patient-centered care within their local communities.

Approach SUD Like a Chronic Disease

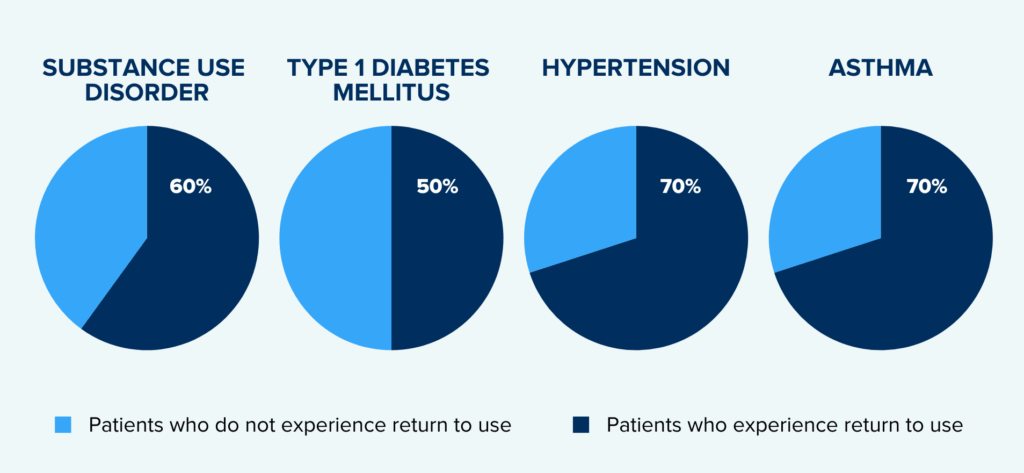

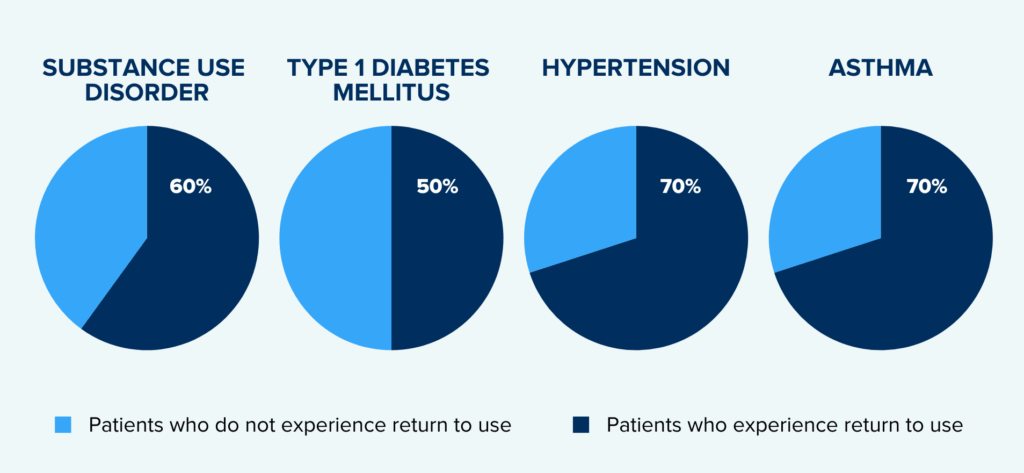

SUD includes similar incidents of recurrence as other chronic diseases like Diabetes and Hypertension. Like those illnesses, early identification of risky substance use, or SUD can be managed successfully by less intensive treatment.

People with substance use disorder experience incidents of return to use just like others do with chronic diseases like diabetes, hypertension, and asthma.12

Screening for Risky Substance Use

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for patients age 18 or older by asking questions about unhealthy drug use. Screening should be implemented when services for accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and appropriate care can be offered or referred.4 Many treatments can be offered by primary care providers. Integrating SUD screening into routine primary care visits also helps normalize conversations about substance use, reducing stigma and encouraging patients to seek help.3

Risky Use Does Not Equal Substance Use Disorder

It is important to recognize that not all patients identified as having risky substance use or experience tolerance to substances, like opioids, have a substance use disorder and in fact, many do not. However, even patients with risky substance use are at risk for adverse health outcomes. Continued risky use may put someone more at risk of progressing to a Substance Use Disorder (SUD).

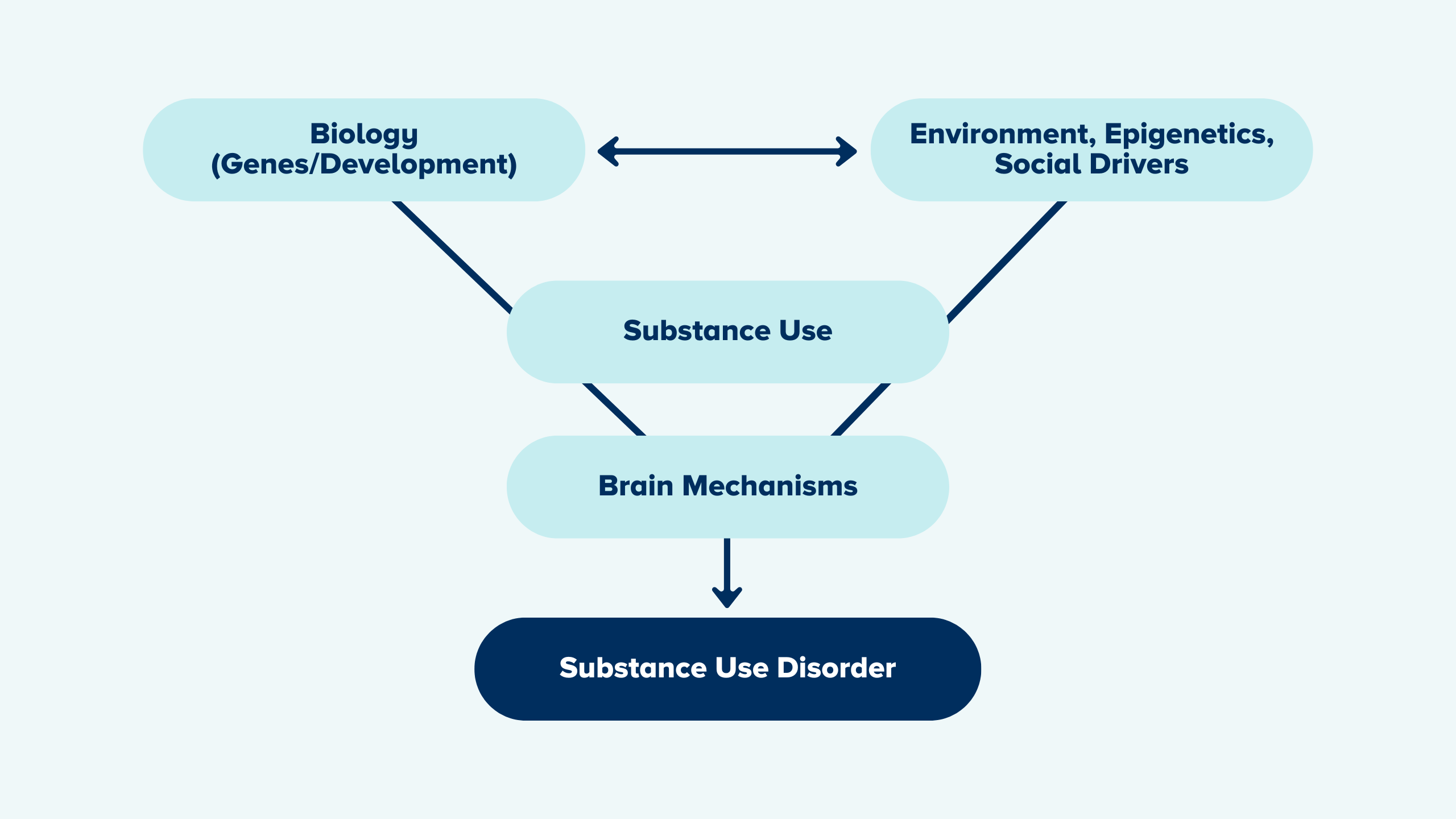

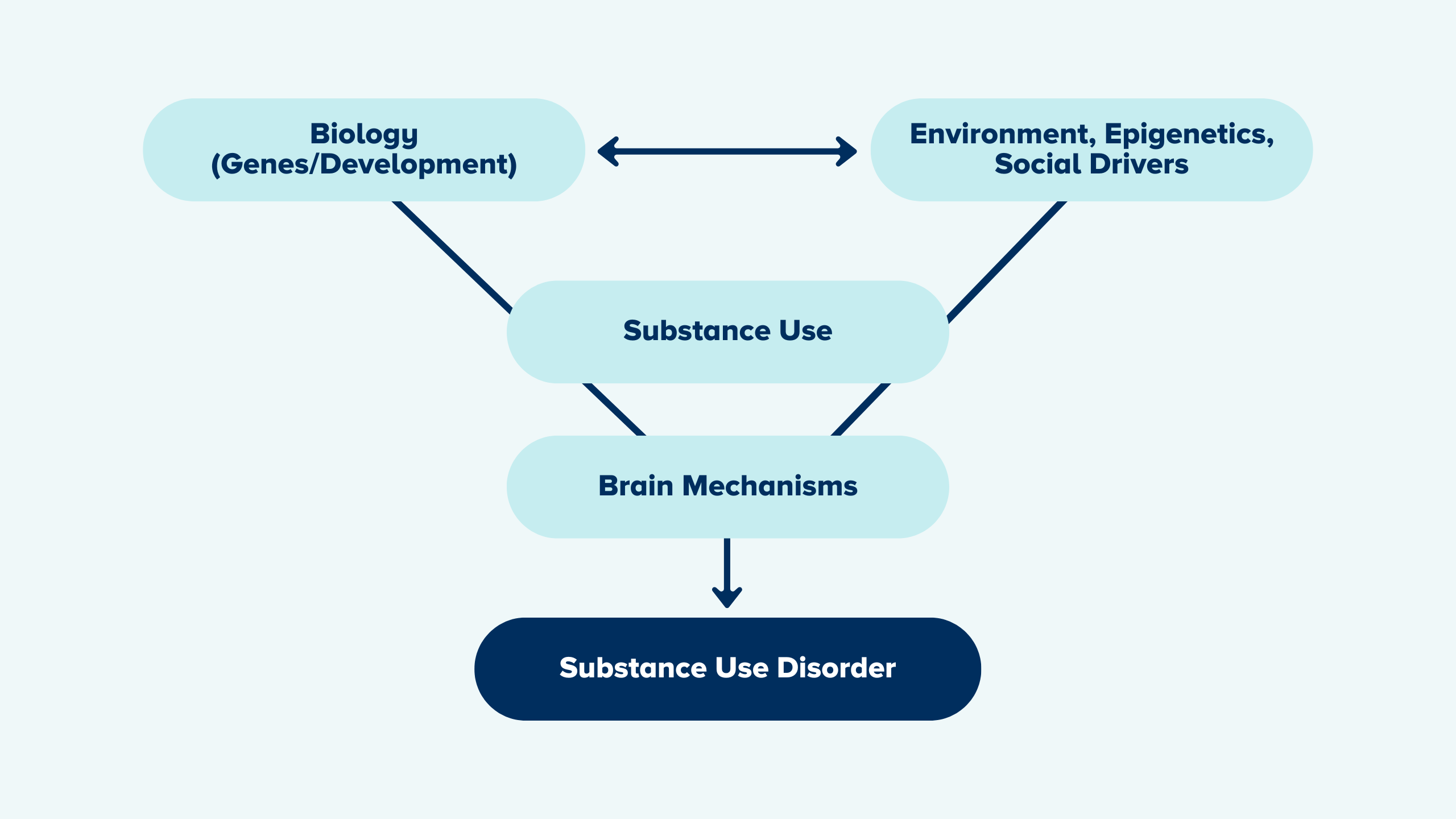

What Shapes a Person’s Risk for Substance Use Disorder?

Whether an individual ever uses alcohol or any other substance, and whether that initial use progresses to risky or problematic use or a SUD of any severity depends on a number of factors:

- An individual’s genetic makeup and other biological factors

- The age of first use

- Psychological factors related to an individual’s unique history and personality

- Environmental factors such as the availability of drugs, family and peer dynamics, financial resources, cultural norms, exposure to stress and access to social supports.

Factors That Can Contribute to Substance Use Disorder

A person’s risk for substance use and developing a substance use disorder is shaped by a mix of biological, psychological, developmental, and environmental factors.

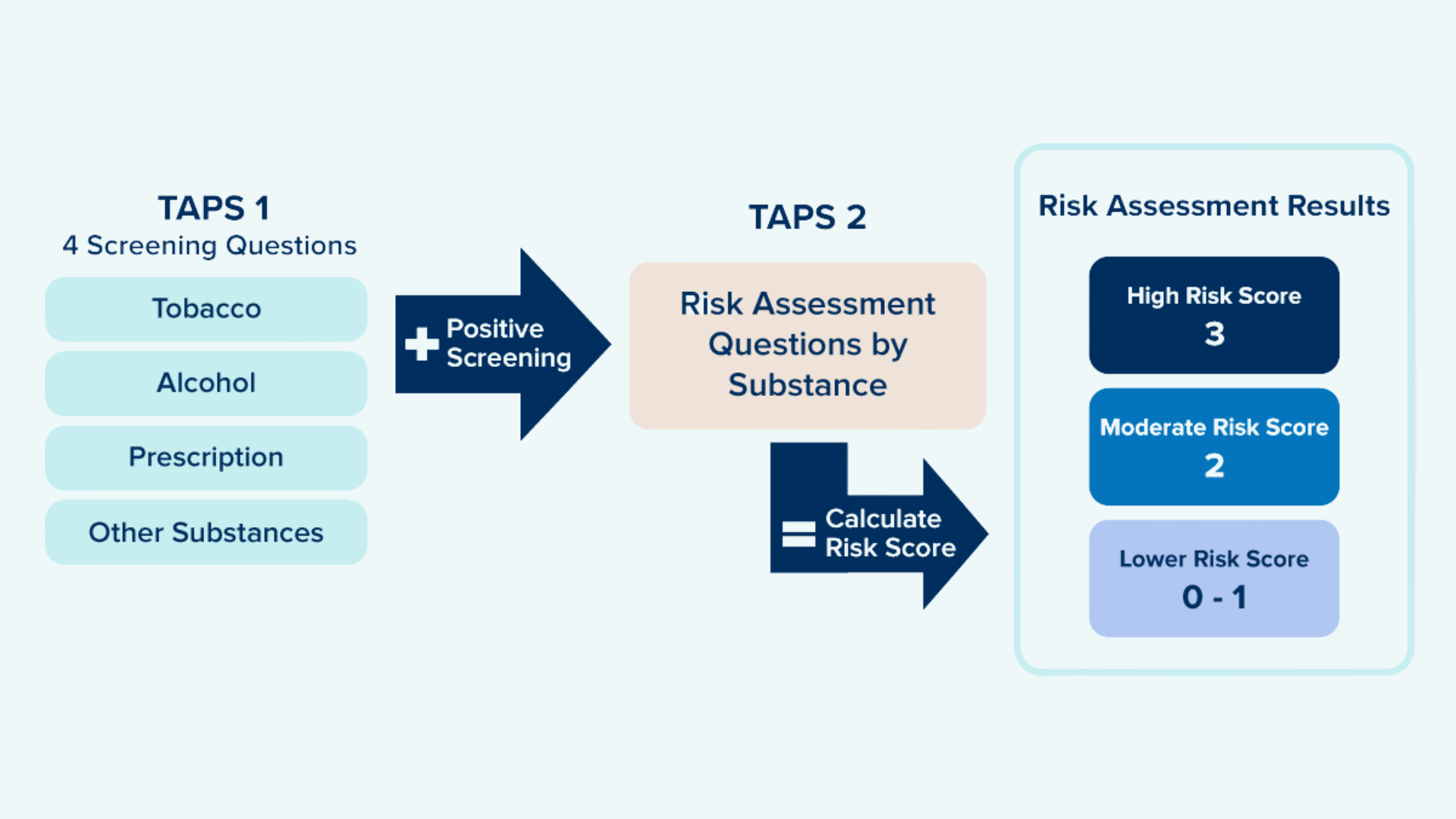

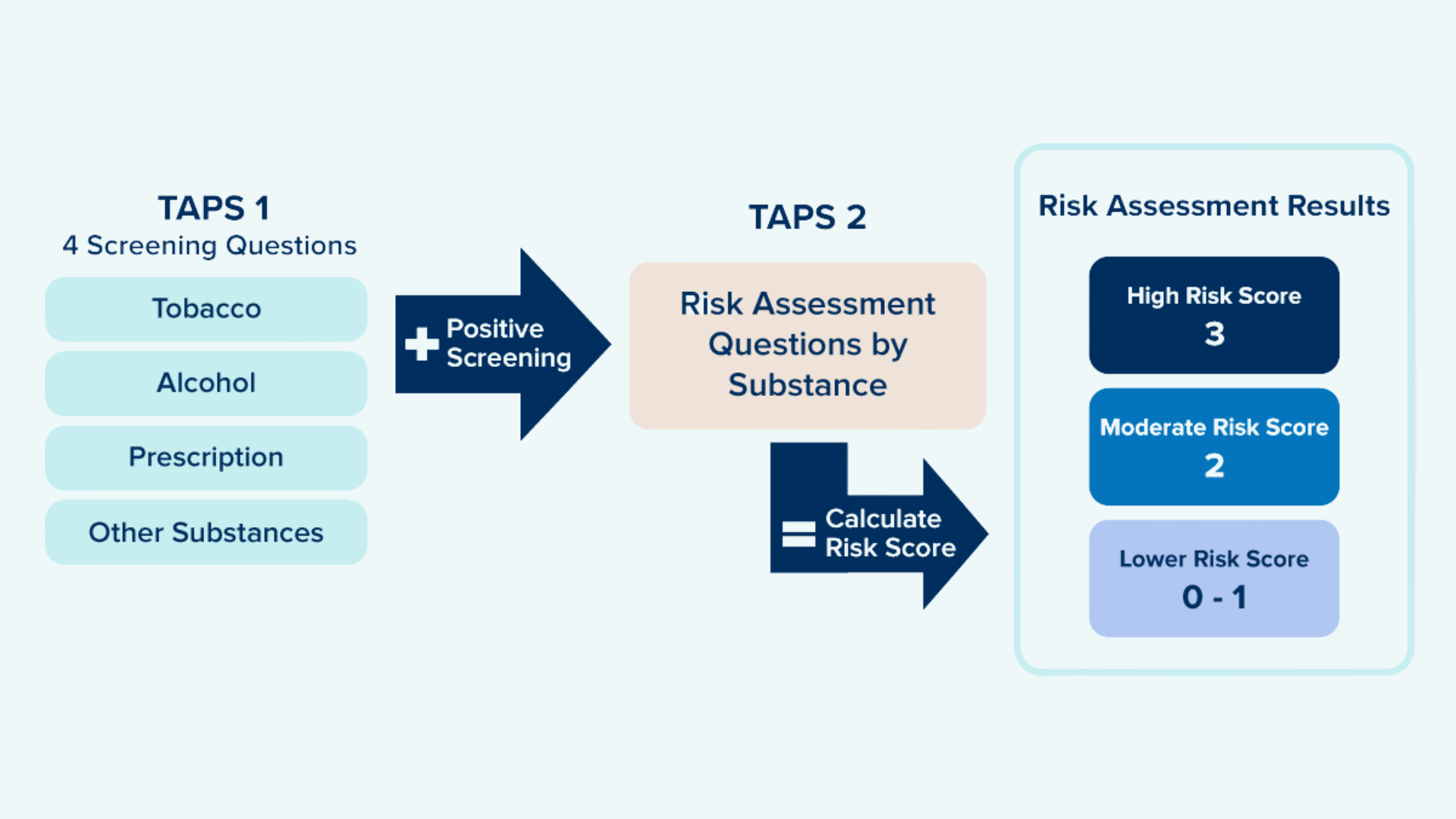

Utilize a Standardized, Validated Instrument to Identify Potential Risky Use

OPEN recommends using the TAPS (Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication, and Other Substance Use) brief, two-part screening tool.

Commonly Used Screening Tools:

Diagnosing a Substance Use Disorder

SUD is formally diagnosed using the DSM-5 criteria and classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

CLASSIFICATIONS:

- Mild: 2-3 of the below symptoms

- Moderate: 4-5 of below symptoms

- Severe: 6 or more symptoms

SYMPTOMS:

- Use in larger amounts/longer periods than intended

- Unsuccessful efforts to cut down

- Excessive time spent taking drug

- Failure to fulfill major obligations

- Continued use despite problems

- Important activities given up

- Recurrent use in physically hazardous situations

- Continued use despite social consequences

- Craving

- Tolerance*

- Withdrawal*

*For substances that cause tolerance or withdrawal when taken appropriately under medical supervision, these two symptoms do NOT count toward a Substance Use Disorder (SUD) diagnosis unless they occur outside of appropriate medical use.

What’s easiest for systems is often times not best for patients; what’s best for patients is what’s typically hard for systems.

Dr. Eliza Hutchinson

Substance Use Disorder Treatment

Each person’s journey with substances and recovery is different. Some are straightforward, but most involve various turns along the way. Prioritize trust, autonomy, and the patient’s communicated treatment goals.

Instead of focusing solely on abstinence, providers can meet patients where they are by offering safer-use strategies, overdose prevention tools, and evidence-based treatment options like medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD). By maintaining an open and supportive relationship—even when patients are not ready to pursue treatment—providers create opportunities for future engagement and improved health outcomes.

Significant disparities and treatment gaps exist!

Despite the effectiveness of treatment, most people with a substance use disorder do not receive any care at all. National data show that only about 10% of individuals with an SUD receive specialty treatment.

Disparities in treatment access also persist across racial and ethnic groups, and systems designed to offer SUD care often involve high barriers and are not easily accessible to everyone who needs them. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), among individuals needing treatment for substance use disorders, 23.5% of White individuals received treatment, compared with 18.6% of Black individuals and 17.6% of Hispanic individuals. While overall overdose rates have decreased slightly, overdose deaths among Black populations continue to rise. These inequities stem from economic barriers, systemic biases, and historical injustices.13

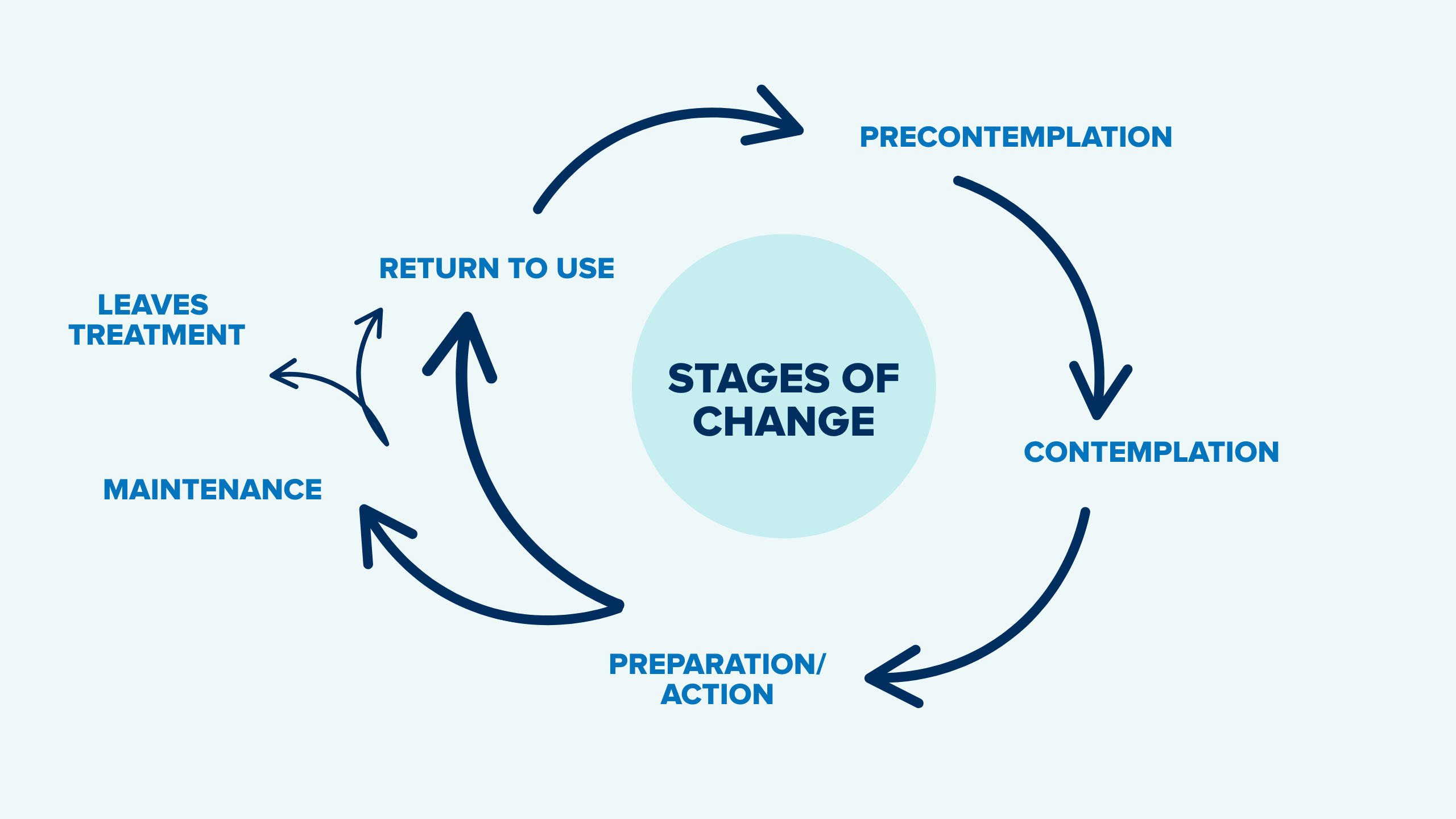

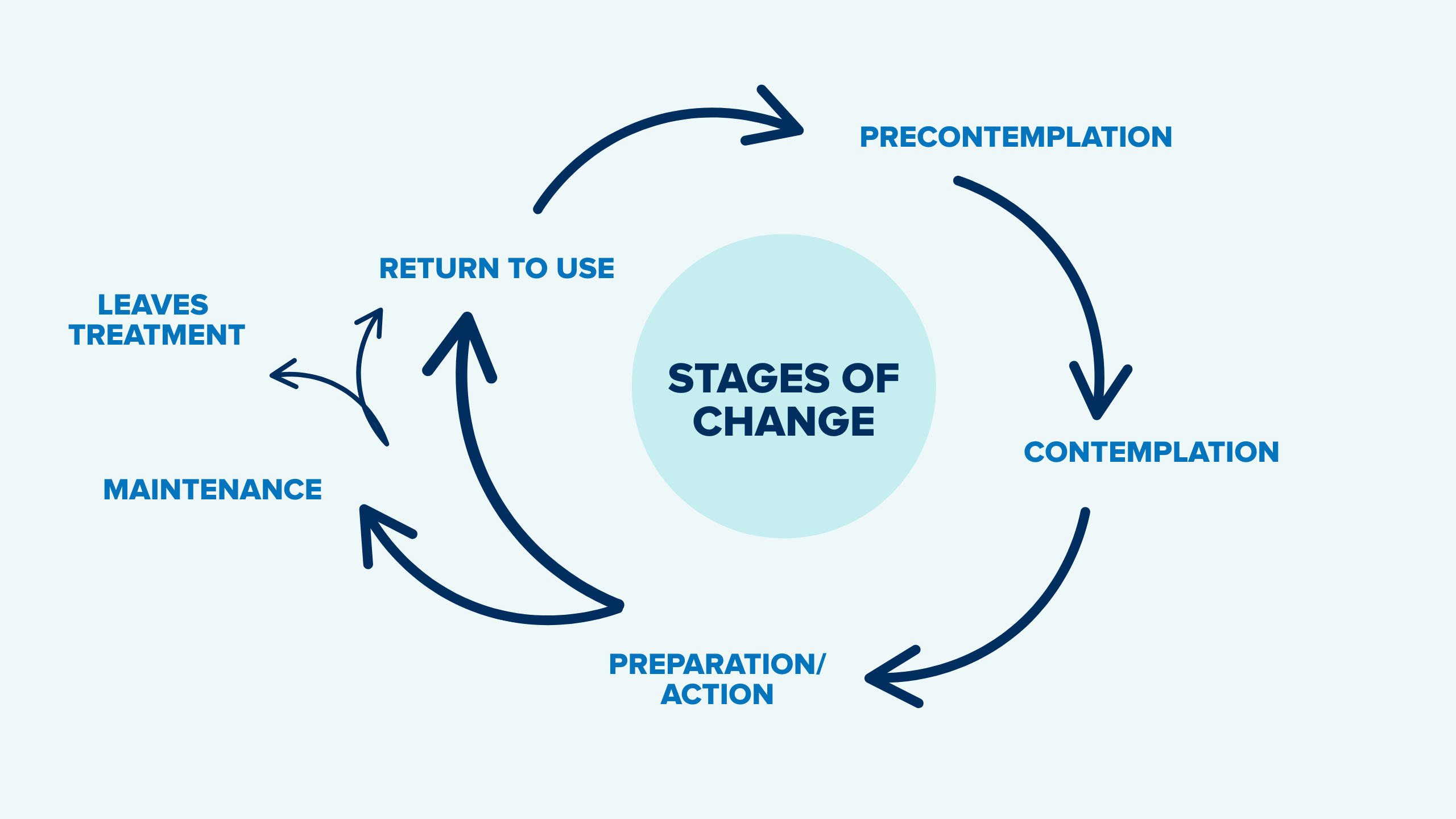

Stages of Change

A Guide for Supporting Behavior Change

The Stages of Change model, also known as the Transtheoretical Model, is a theoretical framework for understanding how individuals progress through a series of stages when changing a behavior. This model is used extensively in health psychology, particularly in the context of addiction and other behavior change interventions. The model recognizes that change is a dynamic and cyclical process. Individuals can move back and forth between stages and may need multiple attempts to successfully change a behavior.

| Stage | Explanation |

| Precontemplation | In this stage, individuals are not yet considering change. They may be unaware of the need for change or believe that the negative consequences of their behavior do not apply to them. The goal for the PCP is to engage the patient, raise awareness, and gently encourage them to start thinking about the possibility of change. |

| Contemplation | Individuals in this stage are aware of the need for change and are thinking about it but have not yet committed to taking action. They are considering the pros and cons of changing their behavior. The goal for the PCP is to help the patient explore their ambivalence, weigh the pros and cons, and build motivation for making a change. |

| Preparation | In this stage, individuals intend to take action soon and may start taking small steps toward behavior change. They are planning to make a change and may seek information or resources to help them. The goal for the PCP is to help the patient develop a clear and achievable action plan, increase their confidence, and provide resources and support to facilitate the change. |

| Maintenance | In this stage, individuals work to sustain the new behavior over time. They develop strategies to prevent relapse and continue with the new behavior. The goal for the PCP is to support the patient in maintaining their progress, reinforce their commitment, and help them develop strategies to manage potential triggers and setbacks. |

| Return to Use | Return to use is not considered a separate stage but a part of the process. It refers to returning to old behaviors after a period of change. This is common and can happen at any stage. The key is to use the experience as a learning opportunity and continue moving forward. The goal for the PCP is to provide support, explore the rationale for return to use, and assist them in developing strategies to get back on track. For example, maybe the person’s medication for opioid use disorder wasn’t at the appropriate dose or they were not able to get to their next appointment for a refill. |

Substance Specific Resources

OPEN has many resources available tailored to various substances and include treatment best practices.

Polysubstance Use Considerations

Polysubstance Use is Common

A study in 2017 found that most US veterans diagnosed with opioid use disorder also have at least one comorbid substance use disorder1. Overdoses involving co-occurring use of opioids and stimulants (like cocaine and methamphetamine) are increasing, and there are significant racial and regional disparities in mortality rates. Non-Hispanic Black Americans have experienced sharper increases in opioid/psychostimulant mortality than non-Hispanic White Americans.2

Treat Co-Occurring Substance Use Disorders Simultaneously

Treatment of combined psychostimulant and opioid use is critical. Patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) and other co-occurring substance use disorders (SUDs) are less likely to be treated with methadone or buprenorphine and less likely to be retained in treatment.5

- The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) recommends continuing buprenorphine to treat OUD even with ongoing use of other substances9

- Evidence supports other substance use decreases with treatment of OUD6,7

- Observational studies supporting the benefit of buprenorphine occurred in real world settings where polysubstance use is common11

- Offer patients treatment for stimulant use disorder (e.g., behavioral treatments/psychotherapies including contingency management) while maintaining medication treatment for OUD (MOUD). If a patient declines treatment for stimulant use disorder, this should not change management of MOUD.

- Assess reasons for co-occurring substance use, behaviors and patterns

Key Considerations for Primary Care

Building a strong referral network is essential for primary care providers (PCPs) to ensure that patients with SUD can access comprehensive, timely, and effective care. Identify a community network to refer and coordinate care for patients who are transitioned to other settings for SUD treatment. SUD treatment levels of care include outpatient behavioral health services, peer recovery support coaches, addiction specialists, residential treatment centers, and support groups. Provide the patient with contact information and assist with scheduling the initial appointment if possible.

1. Identify and Partner with Local SUD Treatment Providers

- Create a directory of local low-barrier SUD treatment programs, including:

- Outpatient medication-assisted treatment (MAT) providers (buprenorphine, methadone).

- Detox and inpatient rehabilitation centers.

- Intensive outpatient programs (IOPs) and partial hospitalization programs (PHPs).

- Peer support and recovery coaching services.

- Vet providers to ensure they align with harm reduction principles and patient-centered care.

- Build relationships through site visits, phone calls, or meetings with treatment providers to understand their services and admission criteria.

2. Integrate Patient-Centered Harm Reduction and Social Support Services

- Partner with harm reduction organizations that provide:

- Syringe services programs (SSPs).

- Naloxone distribution.

- Fentanyl and xylazine test strips.

- Safer use education.

- Connect with social services that assist with:

- Housing and food insecurity.

- Employment support.

- Transportation to treatment.

3. Streamline the Referral Process

- Establish direct referral pathways to make it easier for patients to access care without long wait times.

- Use “warm handoffs” instead of passive referrals—personally introduce patients to the next provider.

- Develop collaborative care agreements with treatment providers to facilitate information-sharing (with patient consent).

- Utilize electronic health record (EHR) integration to streamline referrals and care coordination.

4. Reduce Barriers for Patients

- Work with providers who accept Medicaid, uninsured, and underinsured patients.

- Identify programs that offer low-threshold entry, not requiring abstinence or rigid adherence.

- Ensure referrals accommodate co-occurring mental health disorders and offer integrated care.

- Provide transportation assistance through bus passes, ride services, or mobile clinics.

5. Stay Engaged and Evaluate Referral Success

- Follow up with patients after referrals to check if they were able to access services and if their needs were met.

- Maintain ongoing communication with referral partners to address gaps and improve coordination.

- Seek feedback from patients to ensure referrals are useful, accessible, and effective.

- Join or form regional SUD care collaboratives to share best practices and advocate for expanded services.

References

- Teeters, J. B., Lancaster, C. L., Brown, D. G., & Back, S. E. (2017). Substance use disorders in military veterans: Prevalence and treatment challenges. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 8, 69–77. https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S116720

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2024). Results from the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States (HHS Publication No. PEP24-07-021, NSDUH Series H-59). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt47095/National%20Report/National%20Report/2023-nsduh-annual-national.pdf

- Kaswa, R. (2021). Primary healthcare approach to substance abuse management. South African Family Practice, 63(1), e1–e4. https://doi.org/10.4102/safp.v63i1.5307

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (n.d.). Illicit drug use: Screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-screening

- Winstanley, E. L., & Stover, A. N. (2021). The impact of the opioid epidemic on U.S. state and local government finances. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 16, Article 26. https://ascpjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13722-021-00266-2

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

- Kowalchuk, A., Gonzalez, S. J., & Zoorob, R. J. (2024). Substance misuse in adults: A primary care approach. American Family Physician, 109(5), 430–440. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38804757/

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration & Office of the Surgeon General (U.S.). (2016). Facing addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health – Chapter 2, The neurobiology of substance use, misuse, and addiction. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424849/

- American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM). (2020). The ASAM national practice guideline for the treatment of opioid use disorder: 2020 focused update. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 14(2S Suppl 1), 1–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000633

- Wakeman, S. E., & Barnett, M. L. (2018). Addressing unhealthy substance use in primary care. New England Journal of Medicine, 378(7), 593–595. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29933816/

- De Crescenzo, F., Ciabattini, M., D’Alò, G. L., et al. (2018). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of psychosocial interventions for individuals with cocaine and amphetamine addiction: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 15(12), e1002715. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002715

- McLellan, A. T., Lewis, D. C., O’Brien, C. P., & Kleber, H. D. (2000). Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA, 284(13), 1689–1695. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.13.1689

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf