Surgery can be stressful for both you and your child. This is natural and expected, and some of this comes from worry about the pain after surgery and how it can be managed. These tools will help you talk to your surgeon about pain before your child’s surgery and manage your child’s acute pain following their operation.

Disclaimer: This information is not meant to be applied in cases of chronic pain in children.

Preparing your child for surgery is important to help their surgical experience and recovery go more smoothly.

Have age-appropriate conversations with your child about their planned surgery and what to expect. Consider your child’s anxiety level when talking to them about surgery.

Choose the right time. If your child is anxious, it may be better to wait until a few days before surgery to discuss it with them, as their anxiety may grow as they wait. It is still very important to talk with them about surgery before the event, so they can be prepared.

Encourage feelings of security. Remind your child of the things that will stay the same despite the changes that happen with surgery and recovery. Some of these stable things include family, home, their room, pets, and their school. Help your child keep an attitude that is adaptive, flexible, and hopeful.

Don’t be afraid to talk about pain.

Pain tells your child that their body is healing and that they might need to balance activity with rest. It is an uncomfortable but natural part of recovery. The amount of pain, how long it lasts, and when it peaks varies based on the procedure that the child undergoes. Each child can have a different emotional response to pain as well which changes their pain experience.

Every child recovers from surgery in their own way, and kids who have the same procedure might have completely different experiences of pain. In most cases, the pain will not be permanent and will get better with time and with healing. This is called acute pain. The goal with acute pain is to treat it in a safe way so that children can heal and recover well. They should be able to drink, eat, and sleep as best as possible given their post-surgical condition.

Pain can be managed using over-the-counter medication, prescription pain medication, and non-medication options as part of a pain management plan to be discussed with your surgeon.

Planning For Surgery and Pain Management Worksheet

Making a plan before surgery about how you might address pain can help with recovery and pain control. You should consider both medications as well as non-medication options that have worked well in the past.

Think about how your child reacts to pain and what has helped them deal with pain most effectively in the past. For a young child it can be difficult to understand why they are experiencing pain; physical comfort, such as hugs and snuggles, can be very helpful.

Be sure to consider your own concerns about your child’s upcoming surgery and possible pain. Work to manage these, so you can be a calm, healing presence for your child. This will help them recover and manage their pain. Remember, the goal of pain management is to regulate enough of the pain, so that your child can heal and recover. They should be able to drink, eat, and sleep as best as possible given their post-surgical condition.

After surgery, you might be invited to join your child in the recovery area. This will depend on your hospital’s policy. Know that some children are very upset when they first awaken. This can be a consequence of the anesthesia itself rather than pain. Your child’s recovery team is best equipped to manage this and can answer any questions you may have. Your child may be at home and away from school or daycare for a period of time following surgery, and may require your full-time care while they recover. If your child will miss school, communicate with their teacher before surgery to come up with a plan for their missed homework. If your child is anxious, this will also help reassure them that they won’t fall behind in their work.

Your goal is to support your child and help them be as comfortable as possible. How will you know if your child is in pain? Ask them and watch them. You know your child best and can pick up on any signs that they’re in distress.

Pain might affect their sleep, appetite, and mood. They might wake up more often at night, not want to eat or drink, cling to you, or withdraw from you. For young children, it can be difficult to understand why they are having pain. Encourage and support them. Each child is unique, and their recovery may be different from another child’s. Use what you know about your child to help them recover.

Purchase the over-the-counter medications (Tylenol®, Motrin®, Advil®) that your care team has recommended to use at home.

Buy food and drink that your care team recommends.

Gather things such as toys, music, books, and technology to be used for distraction after surgery.

Take good care of yourself, so that you are able to care for your child. Remember: pain is a typical response to surgery, and if your child has pain, this is the body’s natural way of recovering. It is not a sign that you are failing them as a parent. If there are other members of your household who rely on you for care, try to create a plan that allows you time to focus on your child’s needs after surgery.

Understand that if your child isn’t sleeping well, you probably will not be sleeping well either and may need support. Do not be afraid to ask for or accept help from others. Make a list of things that you could use help with, including:

Marcus loves playing with his friends Olivia and Nora, but one day while they are swinging at the playground he falls and gets hurt. He has to go to the hospital! At the hospital, Marcus meets a dog named Denver who teaches him about pain, how to help the pain feel better, and how to take medicine safely so that Marcus can get back to playing with his friends again.

The book can be read with augmented reality using your smartphone or tablet. The book is available in English or Spanish. Contact Mott-PediatricTrauma@med.umich.edu.

Every child recovers from surgery in their own way, and kids who have the same procedure might have completely different experiences of pain. Pain tells your child that their body is healing and that they might need to balance activity with rest. It is an uncomfortable but natural part of recovery. The amount of pain, how long it lasts, and when it peaks varies based on the procedure that the child undergoes. Each child can have a different emotional response to pain as well, which changes their pain experience.

In most cases, the pain will not be long-lasting and will get better with time and healing. This is called acute pain. The goal with acute pain is to manage it in a safe way, so children can heal and recover well. They should be able to drink, eat, and sleep as best as possible given their post-surgical condition.

Pain can be managed using both medication and non-medication options as part of a larger pain management plan to be discussed with your surgeon.

If your child has risk factors for opioid addiction, including depression, anxiety, current medication use, prior opioid misuse, or a family history of addiction

After your visit, reach out to your surgeon’s office if you have any additional questions.

Below are some questions to consider when meeting with your child’s surgeon. Getting answers to these questions can help you navigate your child’s recovery with more confidence. The answers to these questions will vary based on the surgery your child is having. If your surgeon is using medical language that you don’t understand, ask them to rephrase it using common language.

Your child’s surgeon may recommend using over-the-counter medications (available without a prescription) such as Tylenol® (acetaminophen) and Motrin® or Advil® (ibuprofen).

Tylenol® and Motrin® each work in different ways to manage pain. They can be given together (1).

Give the dose your doctor recommends: It is important to use the dose your surgeon recommends even if it is different from the dose listed on the medication bottle. The dose on the bottle is based on age, but dosing based on your child’s weight may manage pain better.

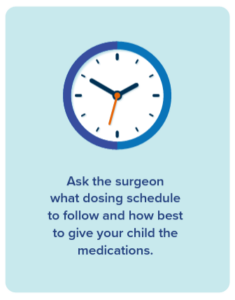

Your team may recommend using these medications on a regular basis (“around the clock”) to manage pain. This means giving your child the medications on a set schedule during the day and even at night. Ask your surgeon what dosing schedule to follow, as well as how to give the medications.

Let your care team guide you: While these medications are usually alternated for management of fever, for pain they can be given together. If you give both Tylenol® and Motrin® together (at the same time), this decreases how often you need to give the medication and can be simpler. If you’re giving the medication around-the-clock, it also means less frequent waking up at night. Follow the instructions your care team gives you in terms of how to use these medications and for how long.

8 AM Acetaminophen and Ibuprofen

2 PM Acetaminophen and Ibuprofen

8 PM Acetaminophen and Ibuprofen

2 AM Acetaminophen and Ibuprofen

8 AM Acetaminophen and Ibuprofen

2 PM Acetaminophen and Ibuprofen

8 PM Acetaminophen and Ibuprofen

This will allow you to manage the pain safely without using more medication than is advised. As with any medications, there are possible serious side effects if used more frequently or at higher doses than prescribed.

You can keep track of medications by making notes on a medication log or on your phone. Write down the name of the medication, the time you gave it, the amount you gave, and when your child can have the next dose. Share this information with anyone else who is also caring for your child, so a dose isn’t accidentally given twice.

Note: Other medications may also contain acetaminophen. Check the labels on any medications you’re giving your child (such as a prescription opioid medication) or other over-the-counter medications to make sure they aren’t already receiving acetaminophen.

| CHECK | |

| For liquid medications, check the concentration on the bottle to make sure you’re giving the correct milligram-based dose. | |

| COMFORT | |

| Have a positive attitude. Be calm, honest, and empathetic but remain in charge. Explain why the medication is helpful. | |

| MEASURE | |

| Only use an oral syringe or medication cup to dose correctly. You can buy these at your pharmacy if they do not come with your medication. Household spoons are not accurate to measure medications. |

|

| PRAISE | |

| Give your child praise when they take the medication. Some children respond well to a small reward such as a sticker or a chart that leads to rewards. | |

| ADAPT | |

| If your child resists taking the medication, use the syringe to squirt small amounts of medicine into the side of their cheek. This prevents gagging and your child is less likely to spit out the medication. Be careful if you are mixing medication with a food your child enjoys in hopes of making it easier for them to take. If you do this, only mix the medication into a small spoonful of food. Otherwise, if they don’t finish it, you won’t know how much medication they took. |

|

| CONSIDER | |

| Ask your pharmacist if you can refrigerate the medication, as the cold temperature may make it easier for your child to take. Sucking on ice chips or a popsicle first will also dull the taste of the medication. You can also follow the medication with a cold drink of something they enjoy. Motrin® can cause stomach upset if taken without food. If possible, give with food or milk. |

(1) Hannam, J. and Anderson, B.J. (2011), Explaining the acetaminophen–ibuprofen analgesic interaction using a response surface model. Pediatric Anesthesia, 21: 1234-1240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2011.03644.x

Opioids are strong prescription pain medications with the potential for serious side effects and complications. Common opioid names include oxycodone, hydrocodone, morphine, and codeine. It is important to know that codeine is not recommended for use in children.

Because of their risks, opioids are not usually the starting point to manage acute pain. Over-the-counter medications and non-medication techniques should be the first things used to manage acute pain. Together, they are often enough to manage your child’s pain. If an opioid is prescribed, it is usually only for management of breakthrough pain after surgery.

Breakthrough pain is severe pain despite over-the-counter medications and non-medication techniques. Know that even if you are using an opioid for breakthrough pain, you should still use the over-the-counter medications recommended and nonmedication techniques. This will allow you to use as little of the opioid as possible.

Some opioids already contain acetaminophen. If this is the case, your child may be unable to take over-the-counter acetaminophen with the opioid. Check the label and discuss this with your pharmacist.

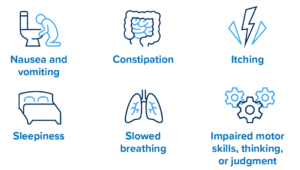

Anyone who uses an opioid is at risk for these side effects:

Children who are overweight or have obstructive sleep apnea or snoring have a higher risk of sleepiness or slowed breathing from an opioid. Do not use opioids to help your child sleep.

| Generic Name | Brand Name |

|---|---|

| Fentanyl | Duragesic* |

| Hydrocodone | Vicodin®*, Norco®* |

| Hydromorphone | Dilaudid® |

| Methadone | Methadose® |

| Morphine | MS Contin®, Kadian |

| Oxycodone | Perococet®*, OxyContin® |

| Oxymorphone | Opana® |

| Tramadol | Ultram®, Ultracet®* |

* Contains acetaminophen (Tylenol). Use caution if you’re also taking acetaminophen separately.

Anyone who uses an opioid, even for a short time, is at risk for dependence, tolerance, misuse, addiction, and overdose. Adolescents are especially at risk for opioid misuse and addiction because the parts of the brain that control impulsiveness and decision-making are still developing. (reference 19) In addition, peer pressure can also affect their behavior. Other factors that increase the risk of opioid use disorder include personal history of depression and/or anxiety and family history of substance use disorder.

When an opioid no longer has the same effect on your child’s pain as it first did, which means they need a higher dose to control pain. For example, if your child is taking an opioid which first worked well for pain, and then later it doesn’t work as well, it does not always mean the pain is worse. Instead, your child may have become tolerant to the opioid.

When your child’s body has started to rely on the opioid to function. This can happen even with using an opioid for a short time period, but the longer your child takes an opioid, the higher the risk. This is one reason why it is important to use an opioid for as short a time as possible. Suddenly stopping an opioid when a person is dependent causes symptoms of withdrawal, such as muscle aches, yawning, runny nose and tearing eyes, sweating, anxiety, difficulty sleeping, nausea/vomiting, and/or diarrhea.

When your child takes the opioid they were prescribed at a higher dose, more often, or for reasons other than which it was prescribed.

When your child develops a brain disease known as Opioid Use Disorder (OUD). People with this condition seek and use opioids even though they are causing them harm.

When your child takes a dose of medication that is too high for them. This affects breathing and can cause your child to stop breathing.

When anyone other than your child gets and uses the prescribed medication. This can happen when you do not safely dispose of an opioid or leave it unattended. Diversion is dangerous because it can lead to misuse, overdose and/or opioid use disorder in others. Sharing or selling an opioid is a felony in the state of Michigan.

Non-medication strategies play an important role in managing pain and reducing anxiety. You can use these strategies, along with the medications your surgeon has recommended, to help your child recover. Using these methods may allow you to decrease use of opioids and avoid their side effects.

|  |  |

| Mindfulness | Special Foods | Art |

| Practicing calm breathing, like belly breathing or square breathing, can help to relax muscles that are tensed because of pain or anxiety. Your child can use their imagination to visualize a place that makes them feel calm, relaxed, and comfortable. | Special foods, such as ice cream or popsicles, can distract your child from their pain by giving them something enjoyable to think about | Art can be a tool for positive coping, a distraction from pain, and an outlet for your child or teen to communicate their feelings. |

|  |  |

| Music | Games & Play | Books |

| Music may be very comforting when your child is experiencing pain or discomfort. Listening to music, singing, or writing songs can help lessen pain and anxiety. | Keeping your child’s mind focused on something else can help reduce their awareness of pain. Helpful distractions can include toys, board games, video games, or movies. | Reading children’s books about surgery and emotions can help your child understand their own pain and feelings better. This may give them a sense of control and decrease their anxiety. Reading your child’s favorite books and stories together can also comfort them |

|  |  |

| Family Time | Sleep | Foods & Hydration |

| Many children are reassured by the presence of their family. Spend time with your child and be a calming presence for them. Some children are relaxed by gentle touch and massage, which can help reduce pain. | Sleep helps the body heal. Allow your child to get the best night’s sleep possible by getting them to bed at their usual time and providing a relaxing and calm environment | Make sure your child is drinking enough fluids and eating as normally as possible while being mindful of any restrictions from your surgeon. Dehydration can worsen recovery and increase pain. Some signs of dehydration in children are: • Dry lips, mouth, or skin • Decreased urination • Lack of tears when crying • Lethargy (decreased energy) |

Learn how to help manage your child’s pain and anxiety after surgery.

Use and share this worksheet with your child’s care team to help prepare and manage pain after your child’s surgery.

A one-page flyer created by the Pediatric Trauma Group at C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital focused on non-medication options for teens.

A document created by Michigan Medicine Child Life providing greater detail on non-medication strategies.